One of Vipassana meditation’s main requests is to realize that you cannot perceive the shape of your body. Meaning, in place of well-defined margins of hands, legs, feet, neck or abdomen, what you’re really able to perceive is marginless tension, pressure, pain, tingling, itching. This has some compelling implications if we consider Hume’s description that what constitutes a person is a bundle of successive images and feelings: to be conscious is to be the subject of an itch.

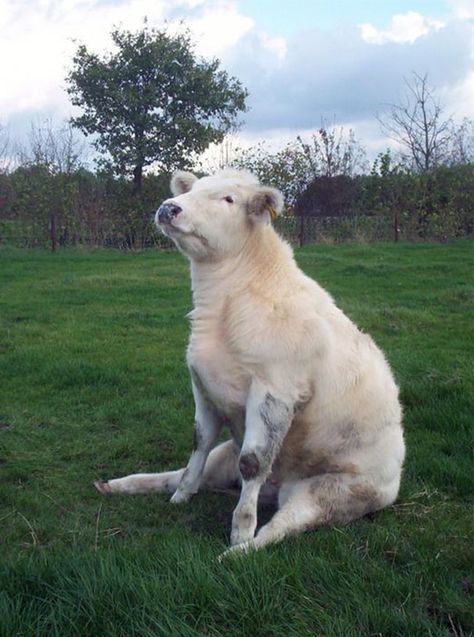

Happily, the idea of animals as conscious beings is no longer contested. However, precisely how animals are conscious and how different species perceive and respond to the world is endlessly speculative. Dogs, for instance, react to their environment with emotional awareness; they move purposefully, recall, build memories, and learn lessons, yet they exist unencumbered within the present moment.

Close your eyes and focus on the sensations of your body, the idea that you can feel its shape and limits must dissipate. This may take a few short sessions of meditation over a couple of days if you’re completely unfamiliar with the practice.

Once you get there, picture any part of your body as something else. What if you had a paw, a tentacle? How would your limb move if it were able to taste or see for itself? Have you ever put a garment that was left out to dry against your lips to check if it’s still wet? Humans don’t have wet receptors on our skin, we make this information up through context clues. I grew up seeing the women in my family test the temperature of babies’ milk on their wrist. Someone told me that’s a lousy method. Giraffes and horses are born walking, but to have legs like that, you would have to invent a new way of hugging. How would you move through the world if you had a stinger? If you were poisonous? If you couldn’t turn your neck but had to protect your back?