To evidence the complexity of play and future trading, I will evaluate them as two future-based systems composed of heterogeneous actors, their interactions, and their emergence, resulting in indeterminacy. Furthermore, I will juxtapose both systems of play and future trading, unraveling the intricacies that define their conception, operation, and influence. By delving into aspects such as the conception of space–speculative temporal space, the importance of rules and free competition, and the role of myths and rituals, I aim to expose the fundamental similarities and differences between these two complex systems and understand how these two models that engage with uncertainty have prevailed.

Play: A Complex System

To evidence the complexity of play and future trading, I will evaluate them as two future-based systems composed of heterogeneous actors, their interactions, and their emergence, resulting in indeterminacy. Furthermore, I will juxtapose both systems of play and future trading, unraveling the intricacies that define their conception, operation, and influence. By delving into aspects such as the conception of space–speculative temporal space, the importance of rules and free competition, and the role of myths and rituals, I aim to expose the fundamental similarities and differences between these two complex systems and understand how these two models that engage with uncertainty have prevailed.

The presence of play in nature as a deeply rooted phenomenon has been frequently explored and highlighted. Huizinga (2014) emphasizes how play extends beyond human culture, as observed in the behaviors of diverse species. From birds’ intricate mating displays to primates’ interactions, the cooperative aspect of play underscores its evolutionary significance as a means of social bonding and communication. Through play, individuals learn to navigate complex social structures, establish hierarchies, and negotiate conflicts, an essential process of mimesis for survival and reproduction in the natural world. This shared inclination towards play underscores its complex role in shaping social dynamics and cognitive development across species.

Firstly, we need to delve into and define the term ‘play,’ an overarching term for the creation of games, to fully grasp its complex features. The etymology of the English word ‘play’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon word plega, which refers to a rapid movement, a gesture, a grasp of the hands, clapping, playing on a musical instrument, and all kinds of bodily activity (Huzinga, 2014). This brings us to our first complex feature, the body and its relationship to others: interactions. Play involves a series of interrelationships and connections, which could be explored in detail in human cognitive and neurological processes—however, I will not focus on this aspect in this paper. Instead, I will delve into the complexity of social interactions among actors who engage in play. Complex systems such as play are characterized by being composed of multiple agents and relationships. Gomes and Gubareva (2020) state that complexity emerges because of the heterogeneous nature of agents, who are not alike; they differ in their preferences, endowments, expectations, hierarchical position, degree of connectivity, and ability to engage in successful interactions, among other features. Play initiates from the idea that you need at least two people, thus the inherent social aspect, and within that condition, both actors bring unique skills and interests that affect the game’s dynamics and overall outcome.

A complementary definition for play comes from the ancient Hindu word for play, ‘Lila’: “…describing all reality as the outcome of creative play. It makes the creation, destruction, and re-creation of everything that cycles in the cosmos the play of the gods” (Pethick, 2021, pp.22-23). Besides the supernatural aspect of the gods and fate, which I will explore below in more detail, this definition suggests that within the seemingly chaotic nature of existence lies underlying features of destruction and creation, spontaneity and structure, and recreation and emergence. This relation between structure and spontaneity mirrors the fundamental tension within complex systems, where order emerges from chaos and how novel patterns arise from interactions among diverse elements. Play is emergent, demonstrating how a set of initial conditions—rules, spaces, time—can affect the execution of the game, and subsequentially, actors may then propel further changes and constantly create new possibilities. “As the interaction occurs, agents learn, adapt, and mutate, leading to a systematic and never-ending evolutionary process where the individual agents and the whole structure are subject to constant and perpetual change” (Gomes & Gubareva, 2020, p.316). Thus, among individual behaviors and interactions lie a series of complex structures and infinite possibilities that influence the heterogeneous actors and the outcome, making it completely unpredictable.

Play’s emergent properties defy reductionism, evident in its interdeteminacy and evolutionary nature. Mihai Spariosu, an expert in human development, states, “Play is one of those elusive phenomena which can never be contained within a systematic scholarly treatise; indeed, play transcends all disciplines” (Pethick, 2021, p.23). Play is a microcosm of the larger complex systems it operates, embodying adaptability that characterizes emergent phenomena across diverse domains of human culture. Play is inherently complex because it is a system whose core is its interrelationships and diverse dynamics while embracing the heterogeneous nature of its agents and emergent properties. This results in a system where uncertainty is at the forefront. By recognizing the complexity inherent in play, we gain insight into its profound significance in shaping human culture, behavior, and cognition, influencing institutions, economic models, and, subsequently, collective narratives of uncertainty, which I will denominate as social fiction.

Fictitious Capital (The Narrative)

Future Trading (The Complex System)

Before delving into the complexity of the future trading system, it is vital to understand Fictitious capital as the collective narrative or concept behind trading. Fictitious capital refers to forms of capital that derive value from the expectation of future income rather than physical means of production or human work. Karl Marx introduced the concept of fictitious capital in the third volume of The Capital. Marx describes: “

“… the value of the capital represented by this paper in the safes of the banker is itself fictitious, in so far as the paper consists of drafts on guaranteed revenue (e.g., government securities) or titles of ownership to real capital (e.g., stocks), and that this value is regulated differently from that of the real capital… the claim on the same revenue is expressed in continually changing fictitious money-capital”…

Fictitious capital encompasses various financial instruments such as stocks, bonds, derivatives, and other securities whose prices are based on expectations of future profits or cash flows. For the purpose of this essay, I will focus specifically on future trading as an economic system but highlight how this concept of Fictional Capital permeates its complex nature.

The term speculation can be traced back to finance and refers to purchasing an asset with the hope that it will become more or less valuable in the near or far future. Speculation began to gain relevance in future trading, where contracts, known as futures contracts, are traded on organized exchanges and are used to invest based on price fluctuations. “Futures trading tends to emerge and persist, especially in commodities which are subject to exceptionally large price fluctuations, arising from unpredictable variations in production, from other supply uncertainties, and from relative inelasticity of consumption demand (Working, 1953, p.327). Future trading is a complex system that can be evaluated by its inherent properties of multiple agents and networks and emergent properties—which can be observed in its market dynamics, investor behavior, regulatory frameworks, and macroeconomic conditions, making them intricate systems that are challenging to understand and predict fully.

The complex nature of future trading involves various actors with distinct motivations, knowledge, strategies, and bets. Today’s traded commodities in the future market primarily include oil, coal, and electricity; agricultural commodities, such as corn and wheat; and metals, such as gold, silver, and steel (Fernando, 2023). However, future trading may also include cryptocurrencies; equities futures based on stocks traded in the market; interest rate futures, bonds against future changes in interest rates; and stock index futures with assets as the S&P 500 Index. The future trading system is compromised by nonspeculators or “hedgers” and, on the other end, the speculator, playing what many consider a gambling game—betting into the future. Future trading establishes a contract between the buyer and the seller at a predetermined future date and price. According to Working (1953, p.325), hedgers buy the commodity or asset because the price negotiated is speculated to be lower relative to the futures price. Therefore, they manage risk and avoid getting charged a higher price in the future. If the market prices decline, traders can buy back the contract at a lower price, profiting from the difference. Additionally, traders may purchase a futures contract expecting the price to rise above the original contract price at expiration, and thus, there is a profit when sold.

Being an economic market with multiple agents makes it evidently complex: “Given the multiplicity of involved agents and a series of obstacles that curtail the communication potential across the various players, at each period in time, market participants must be selective when choosing with whom to interact.

This choice is, in principle, guided by rationality but is also subject to various constraints” (Gomes & Gubareva, 2020, p.322). The inherent unpredictability of human behavior, coupled with the nonlinear interactions between market participants, contributes to the complexity of this system, which cannot be fully understood by strictly analyzing its individual parts. Furthermore, the relationship and influence between different financial instruments and markets challenge the behavior and outcomes and—while being part of an open competitive market—other macroeconomic dynamics come into play, economic, political, social, and even environmental, influencing and shaping the outcome unpredictably, leading to continuous fluctuations and feedback loops.

Overall, the complexity of future trading and the concept of Fictitious Capital arises from the intricate relationships between agents, the adaptive nature of markets, but more so the ever-evolving socio-economic landscape in which they operate, specifically the surge of new technologies and regulatory changes that continuously reshape the system, adding layers of complexity and leading to emergent properties. According to Gomes & Gubareva (2020), markets are evolving networks influenced by adapting individual behaviors; fundamentally, markets are the primordial example of a complex system. Furthermore, the relationship between future trading and fictitious capital is based on the future, unpredictability, and fluctuation, thus embracing the possibility of emergent behavior. “All problems of choice in the economy involve something that takes place in the future, perhaps almost immediately, perhaps at some distance of time. Therefore, they involve some degree of not knowing.” (Arthur, 2013, p.3). As a complex system, future trading lies in the interconnectedness within financial markets and their inherent nature of engaging in speculation by betting on future assets. Future trading is a complex system, and it is a model rooted and dependent on future fluctuations and emergent behaviors, making the unpredictable its core.

Measuring Uncertainty

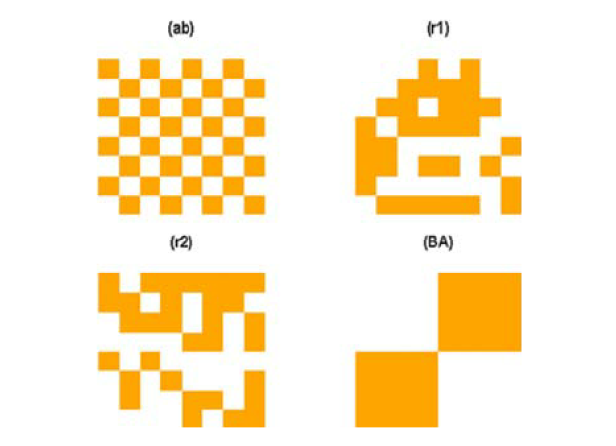

Among the studies to identify uncertainty, Claude Shannon’s entropy is vital and uses play within his experiment. The study was initiated in 1950 by programming a computer to play chess and identifying entropy as a measure of randomness or surprise. It alluded to how chess openings characterized by higher entropy manifest greater complexity and dynamism, offering players many possibilities (see Figure 1-2).

Figure 1. Claude Shannon with his machine completed in 1949, which he referred to as Endgame and Caissac. Shannon referred to chess as not only fascinating in its own right but also a tool for thinking rigorously and attacking other problems of a similar nature and of greater significance and complexity (Soni, 2017).

Figure 2. Didier (2009) studies and displays chessboard configurations and how they have the same normalized Shannon entropy, H u = 1 : (ab) normal Chessboard with a regular spatial structure, its initial condition; (r1 and r2) random permutations of the 64 cells; (BA) another well-structured chessboard permutation.

Thus, by discerning the entropy levels inherent in different opening variations, players can strategically tailor their choices to align with their playing styles, fostering adaptability and informed decision-making in navigating diverse game positions.

Speculative Temporal Space (STS)

A complex feature of play and future trading that I will explore is what I will denominate as speculative temporal space (STS), an essential characteristic among two complex systems ruled by uncertainty and future fluctuations or emergence. Whether it is a playground, stadium, website, board, or even an imaginary realm, play frequently creates its own space, temporarily establishing its own boundaries and limits (see Figure 3-5). Subsequently, financial markets, including future trading, also operate within designated spaces—be it physical trading floors or virtual platforms—and could also be considered STS, where norms and the notion of time govern differently and independently from the “outside” world, influencing the space and its interactions.

The concept of speculative temporary space was inspired by Israel Yizhar’s writing, which Shaul Setter later denominated as speculative temporality: “This speculative temporality conjures a realm wherein that which had already occurred in empirical reality and historical time is negated, a realm wherein the happening of the event—or, more accurately, its having already happened—ceases. It constitutes a different temporal axis, which does not abide by a linear, developmental, progressivist movement of time” (Setter, 2012, p.45). This concept encompasses both play and financial markets as future-based systems. It enriches our understanding by introducing an alternative temporal mode that challenges linear conceptions of time and history. It challenges the conventional progression of time, conjuring a realm where past events do not influence the development of present events and where alternative worlds are imagined. Games have a time limit, be it 90 minutes in a football game or until someone wins over the rest, as with most board games. Accordingly, with future trading, there is also a designated time when the trading floor opens and closes. Therefore, both activities run independently, under their own constraints, and are not affected by the notions of time outside the specific STS. It is its autonomous zone.

Trading, on the other hand—with capitalism being so tightly woven into our social fabric—has demonstrated to have direct consequences on tomorrow’s events, as evidenced by the multiple economic crises that have transformed generations to come. Moreover, Lefebvre (1992, p.111) states that the conception of space always comes hand in hand, not only with the adoption of another god or myth but with a whole new system of measurement, as with time. This notion of self-sustaining measurements is evident in play—with points, sets, matches, wins vs. losses—or in future trading with indexes, spot prices, shares, or GDP (see Figure 6-7). A strong sense of unpredictability characterizes this temporal aspect and independent conception of time; it aligns with the speculative nature of play but also with financial markets, where traders anticipate future outcomes and engage in activities that transcend empirical reality.

Figure 3. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange is the arena primarily for Future Trading, a Speculative Temporal Space.

Figure 4. A Wicca ritual magic circle creates space through interactions, as seen in the popular children’s Ring Around the Rosie game.

Figure 5. A playground—a delineated Speculative Temporal Space.

Play is set within certain limits of time and place, where play controls its own course and meaning, begins, and ends over a set time. “The arena, the card–table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, the court of justice, are all in form and function play-grounds. All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart” (Huzinga, 2014). Just as play marks a spot for its enactment, financial markets delineate spaces where transactions occur. These can be traced back to street markets or the Acropolis: social spaces for transactions and exchanges, creating temporary worlds within the broader societal context. This spatial separation and arrangement influence perceptions and behaviors within these spaces. Moreover, understanding the particular nature of the STS allows us to grasp their complex behavior, networks, and evolution:

“Each market, over the centuries, has been consolidated and has attained concrete form by means of a network: a network of buying- and selling-points in the case of the exchange of commodities, of banks and stock exchanges in the case of the circulation of capital, of labour exchanges… The corresponding buildings, in the towns, bear material testimony to this this evolution. Thus, social space, especially urban space, emerged in all its diversity (Lefebvre, 1992, p.86)”.

Therefore, it emphasizes why both systems are complex since space is not merely a physical place but rather a product of social relationships and practices. It is the outcome of a sequence of operations and dynamics, encompassing interrelationships in their coexistence and simultaneity—in order and chaos—it cannot be reduced to a simple thing.

Furthermore, understanding space as a causal factor is essential in capitalist practices, underlining its system of rules and power, which I will delve into in the next chapter. “Capitalism and neo-capitalism have produced abstract space… Within this space, the town—once the forcing house of accumulation, fountainhead of wealth, and centre of historical space—has disintegrated (Lefebvre, 1992, p.53). Understanding these dynamics of what we classify as a Speculative Temporal Space provides insights into how space influences the conception, perception, and outcome of the activities of play and trading. It highlights the complex nature of spaces as a social, temporal, and emergent phenomenon.

Figure 6. Points, games, and sets comprise the independent measurement system in a tennis match.

Figure 7. The stock exchange’s independent system of measurement is composed of the ticker letter symbols, which identify the company, the number of shares traded, the price per share, whether the stock has increased or decreased compared to the previous day, and the change amount, which is the price difference from the previous day’s close.

Rules: Initial Conditions, Norms, and Free Competition

The presence of rules constitutes an essential feature of both play and trading. Rules serve as an initial condition for systems of emergent behavior and uncertainty. Rules as structured frameworks conceive spaces of open participation but also encapsulate broader themes of norms, governance, agency, and power. In both play and future trading, rules serve as normative constructs that trace the limits of what is allowed, assigning roles, stating the criteria for success, and delimiting the space where the competition unfolds—which we previously denominated as Speculative Temporal Space. Similarly, rules in financial markets take the form of laws, contracts, and institutional protocols governing trading activities, market operations, and investor behavior to establish an equitable or perceived open market for all participants. In the system of future trading and play, rules and initial conditions are essential to engage with uncertainty in order to not fall into a space of utter chaos.

The rules governing both games and financial trading establish the parameters within which participants operate, delineating actions, constraints, and objectives. Searle (2010) explains how most game rules have to do with rights and obligations by giving the example of a baseball game where the rules allow the batter to swing at the ball but do not require the player to swing. Moreover, after the batter gets three strikes, they must leave and let someone else bat. Furthermore, he explains that the aim is winning. However, several rights and obligations are conditional: “Thus if a batter has one strike or three balls, that does not so far give him any further rights or obligations, but it establishes conditional rights and obligations: two more strikes and he is out, one more ball and he is walked to first base. Such conditional rights and obligations are typical of institutional structures” (Searle, 2010). Consequently, individuals develop capacities and adapt according to the game’s rules, leading to unpredictable results emerging from the interaction of both agents and the constraints of space and time (see Figure 8-9).

Figure 8. A meme portraying how the game UNO and its rules have been broken, appropriated, and transformed by its players over time.

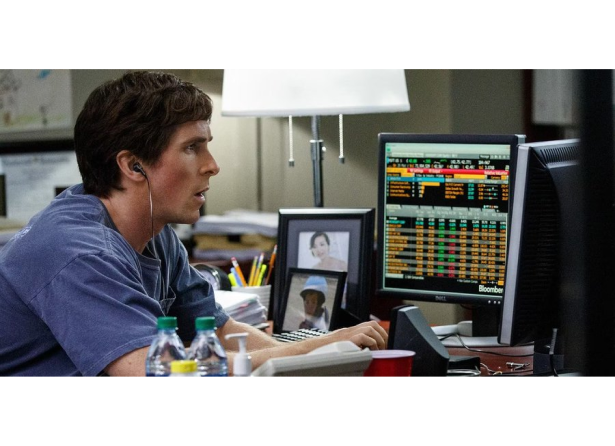

Figure 9. The film The Big Short showcases the character Michael Burry, who predicts the housing market collapse in the mid-2000s and thus creates a new strategy to sell positions, assuming that housing prices will drop, betting against the big banks. His unconventional and risky financial strategies showcase how the rules serve only as an initial condition and adapt, mutate, and emerge from each actor’s predictions.

Regarding future trading, since it is an economic model that exemplifies fictitious capital, no product is sold; instead, a contract, essentially a rule book as in play—which is mutually agreed upon by its agents. One critical aspect and rule in future trading is the management of expiry dates, where traders must monitor and obey contracts as they approach expiration to mitigate potential losses. Other aspects that factor in are the contract size, contract value, and tick size, which dictate the minimum price change of a contract. Within institutional contexts, rules are pivotal in guiding behavior and shaping social norms, even when individuals may not consciously adhere to them—commonly known as cheating. While some may consciously follow established rules, others may navigate institutional environments instinctively, relying on an internalized understanding of appropriate conduct. Searle (2010) mentions that setting rules is associated with his expression of social fact, which refers to any fact involving a collective intentionally, mutually agreed-upon contracts essential for human cooperation. Thus, it highlights the causal significance of constitutive rules among a complex system, which sets a series of initial conditions but simultaneously embraces certain emergent behaviors and the multiplicity of outcomes.

Conversely, free competition represents the ethos of play and trading, fixing a fair space for engagement and autonomy to play with uncertainty and chance but within prescribed bounds. It considers that something is at stake, and there will be winners and losers in the end. In play, free or open participation encapsulates the principle that individuals can exercise their agency, pursue their objectives, and apply their strategies. In financial markets, free competition involves the same principles but, additionally, the efficient allocation of capital that subsequently affects other economic markets, growth, and innovation on a micro and macro scale. The symbiotic relationship between rules and free competition underscores the complex relationship between order and chaos, constraint and freedom.

Myth and Rituals – Social Fictions

Myths and rituals are foundational aspects of human culture, deeply embedded in societal norms and institutions, and essential for human cooperation. Both coexist and hold significance in the complex domains of play and future trading to guarantee social bonding and cope with uncertainty. Rituals serve as vehicles for collective narrative and are pivotal in shaping perceptions, generating engagement, following rules, and maintaining order. From rites of passage to expressions of unity, rituals and myths exemplify the symbolic significance of play and trading, influencing social identities and reinforcing cultural values, and how myths are social mechanisms for engaging with spaces of uncertainty. Myths transcend ordinary time, providing a perspective that allows us to explore how our beliefs, ideologies, and desires are shaped and how they persist over time. According to Lévi-Strauss (1955), a myth is historically specific and ahistorical, meaning it is timeless. Myths are collective narratives that occur outside the traditional conceptions of time. This concept of myth is consistent with the previous notion we explored of Speculative Temporal Spaces: how play and trading share this characteristic of conceiving temporal spaces with autonomous notions of time and social norms.

Among myths lies the presence of rituals in play and future trading, highlighting its importance as a mechanism for navigating uncertainty and instilling a sense of control amidst fluctuations in a setting of exchange, engagement, and competition among heterogeneous agents. Gustafson (2015) describes how rituals are seen evidently in financial settings, such as Wall Street, where the day commences and concludes with bell-ringing, reminiscent of religious practices, and how, during times of economic crises, such rituals and prominent leaders/experts’ priests’ take on added importance, providing participants with a sense of predictability or reassurance in the face of chaos (see Figure 11). This ritual also delineates their autonomous measurement of time, the beginning and the end among the Speculative Temporal Space, which is also characteristic of play. Furthermore, in play, we see how games are linked to rituals: “A marble game may be a rite of passage for a youngster in the schoolyard as he tests his skill against another player… students flipping baseball cards celebrates a rite of unity. A poker game or pinball game may serve as a rite of reversal, a time of release…” (Smith, 1984, p.132). In play and trading, rituals serve as vehicles for collective narratives to generate social cohesion, highlighting the meaning behind each activity and its endurance over time. Ritual is embodied in play and trading by generating meaning and reflecting the participants’ beliefs about prosperity, risk, and control, transforming the incomprehensible—the social fiction—into the comprehensible in a system of emergence and uncertainty

Figure 10. Devidasa of Nurpur. (1694-1695). Shiva and Parvati Playing Chaupar: Folio from a Rasamanjari Series. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 11. The ringing of the bell on Wall Street is used in other financial settings to signal the start and close of trading. The bell is reminiscent of religious practices but is also frequently used in school playgrounds, where the bell is rung to announce the end of break or playtime.

Conclusion

By analyzing and comparing the complex systems of play and future trading, we can depict how deeply rooted they are in culture, human behavior, social norms, and economic models. By exploring speculative temporal space, rules, free competition, and the role of myths and rituals, it becomes evident that both play and future trading operate within systems characterized by heterogeneous agents, emergent properties, interactions, and essentially unpredictability. Exploring the complexities of play and future trading is valuable in recognizing their profound influence and impact on each other in shaping social fiction models that generate a sense of order among games of uncertainty.

Figure 12. Ignacio Gatica. (2023). Stones Above Diamonds (detail). This installation comprises credit cards adorned with images of boarded-up banks in Santiago, Chile, during the protests of 2019 and 2020. Each card contains encrypted messages sourced from gra ti tags, which, when swiped, disrupt the stock market feed with street poetry. It is a subversive play-like artwork emphasizing collectivity in resistance to financial institutions. Moreover, this phrase highlights the essential notion of fictitious capital, exposing and negating the myth that markets are stable, fair, accessible,

References

- Arthur, B. (2013). Complexity Economics: A different framework for economic thought. In Complexity Economics. Oxford University Press.

- Dusak, K. (1973). Futures Trading and Investor Returns: An Investigation of Commodity Market Risk Premiums. Journal of Political Economy, 81(6), 1387–1406. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1830746

- Entropy in the opening. (2022, June 5). lichess.org. https://lichess.org/@/CheckRaiseMate/blog/entropy-in-the-opening/sBebftmy

- Fernando, J. (2023). Spot Commodity: What It is, How It Works, Example. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/spotcommodity.asp

- Fernando, J. (2024, March 20). What is futures trading? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/futures.asp

- Gomes, O., & Gubareva, M. (2020). Complex systems in economics and where to find them. Journal of Systems Science & Complexity, 34(1), 314–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11424-020-9149-1

- Gustafson, S. (2015). At the Altar of Wall Street ([edition unavailable]). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. https://www.perlego.com/book/2015682/at-the-altar-of-wall-street-the-rituals-myths-theologies-sacraments-and-mission-of-the-religion-known-as-the-modern-global-economy-pdf

- Hirsh, Jacob & Mar, Raymond & Peterson, Jordan. (2012). Psychological Entropy: A Framework for Understanding Uncertainty-Related Anxiety. Psychological Review. 119. 304-320. 10.1037/a0026767.

- Herrera, R. (2014). A Marxist Interpretation of the Current Crisis. World Review of Political Economy, 5(2), 128–148. https://doi.org/10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.5.2.0128

- Huizinga. (2014). Homo Ludens ILS 86 (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1663771/homo-ludens-ils-86-pdf

- Ignacio Gatica reifies The abstractions of Global capitalism. (2024, April 24). Frieze. https://www.frieze.com/article/ignacio-gatica-sujeto-cuantificado-quantified-subject-2023-review

- Keynes, J. M. (1930). A treatise on money. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA01101787

- Lefebvre, H. (1992). The production of space. Economic Geography, 68(3), 317. https://doi.org/10.2307/144191

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1955). The Structural Study of myth. The Journal of American Folklore, 68(270), 428. https://doi.org/10.2307/536768

- Marx, K. (1894). The Capital: Volume III: The process of capitalist production as a whole (F. Engels, Ed.). https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-III.pdf

- Pethick, P. (2021). Power of Play: How play and its games shape life. PlayLab Publishing.

- Robinson, W. I. (2023). The Future of Global Capitalism: Crisis, Financialization, and Digitalization. In M. B. Steger, R. Benedikter, H. Pechlaner, & I. Kofler (Eds.), Globalization: Past, Present, Future (1st ed., pp. 306–319). University of California Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.7794627.23

- Searle, J. (2010). The Construction of Social Reality ([edition unavailable]). Free Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/779804/the-construction-of-social-reality-pdf

- Smith, T. (2022). How to trade Futures: platforms, strategies, and pros and cons. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/how-to-trade-futures-5214571

- Smith, J. F., & Abt, V. (1984). Gambling as Play. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 474, 122–132. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1044369

- Soni, J. (2017, August 16). The man who built the chess machine. Chess.com. https://www.chess.com/article/view/the-man-who-built-the-chess-machine

- Working, H. (1953). Futures Trading and Hedging. The American Economic Review, 43(3), 314–343. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1811346

Image References

- Figure 1: Soni, J. (2017, August 16). The man who built the chess machine. Chess.com. https://www.chess.com/article/view/the-man-who-built-the-chess-machine

- Figure 2: Leibovici, Didier. (2009). Defining Spatial Entropy from Multivariate Distributions of Co-occurrences. 392-404. 10.1007/978-3-642-03832-7_24

- Figure 3: Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Walsh Group. https://www.walshgroup.com/ourexperience/building/datacenters/chicagomercantileexchange.html

- Figure 4: Wright, W. (2021, June 4). How to cast a Wicca Ritual Magic Circle. The Not so Innocents Abroad. https://www.thenotsoinnocentsabroad.com/blog/how-to-cast-a-wicca-ritual-magic-circle

- Figure 5: Play & park structures: commercial playground equipment. (2022, January 11). PlayCore. https://www.playcore.com/brands/play-and-park-structures

- Figure 6: Brady, Jonathan. Andy Murray beat Novak Djokovic in the 2013 Wimbledon men’s singles final. https://www.tennis365.com/wimbledon/on-this-day-andy-murray-wins-first-wimbledon-mens-singles-title-2013

- Figure 7: Nasdaq’s stock is down after it priced a stock offering of nearly 27 million shares from one of its shareholders. GETTY IMAGES/ISTOCKPHOTO. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/nasdaqs-stock-drops-after-1-6-billion-offering-from-stock-exchange-parent-e0b898e6

- Figure 8: Uno you cannot play a +2 on a +2 [Digital image]. (2020). https://www.reddit.com/media?url=https%3A%2F%2Fi.redd.it%2F74eagwqw50t51.jpg

- Figure 9: It’s now cheaper to rent than buy a starter home in every one of the country’s 50 largest metropolitan areas according to MW [Digital Image]. (2024). https://twitter.com/burrytracker/status/1775557622881472898

- Figure 10: Devidasa of Nurpur. (1694-1695). Shiva and Parvati Playing Chaupar: Folio from a Rasamanjari Series. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Figure 11: Taking stock: What it’s really like to ring the NYSE bell. (2021). https://www.nyse.com/taking-stock/what-its-really-like-to-ring-the-nyse-bell

- Figure 12: Ignacio Gatica reifies The abstractions of Global capitalism. (2024, April 24). Frieze. https://www.frieze.com/article/ignacio-gatica-sujeto-cuantificado-quantified-subject-2023-review